In search of the thylacine..

New media rumors revive an "old" question: is the thylacine still alive?

By Sofia Solovieva, SPbU Biologist

Photo: Thylacine at Beaumaris Zoo, 1936 - Credit: Tasmanian Archives, NS4371-1-1063

The Thylacine Awareness Group, is an amateur no-profit organization created to find an enigmatic marsupial that officially gone extinct 85 years ago. Neil Waters, the group’s president, claimed that one of his camera traps captured photos of three specimens of Thylacinus cynocephalus, two adults (a female and a male) and a smaller creature, probably a cub.

Thylacines, otherwise known as “Marsupial wolves”, “Tasmanian tigers” or “Tasmanian wolves”, are considered extinct since 1936. The last specimen was a young male called Benjamin, held at Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo, located on the Queens Domain in Hobart, Tasmania. One of the zoo keepers forgot to let Benjamin back into his shelter, it was a cold night in August and the thylacine, the last one, died due to the rigid temperatures.

The Tasmanian Government acknowledged that thylacines were on edge of extinction in 1901, due to hunting and competition with other species (especially with feral dogs). They were also threatened by new foreign diseases brought to Tasmania by British colonization. For 35 years, the Government did nothing to protect this endangered species and when, on 10 July 1936, the protection was granted, it was too late. 59 days later the last thylacine, Benjamin, was found deceased by the zookeeper.

Thylacinus cynocephalus

"The Zoological Society possessed three individuals of this extremely curious and interesting animal, the only specimens which have ever reached Europe alive...common in more remote parts of Tasmania, where it is called by the names of "Tiger" and "Hyaena" indiscriminately..."

Philip Lutley Sclater, zoologist.

Photo: Thylacines, Male and Female, in the National Zoo Washington D.C. - Credit: E.J. Keller, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Thylacinus cynocephalus was the top terrestrial predator in Tasmania until British colonization and the only modern representative of the family Thylacinidae. These carnivorous marsupials were 100-130 cm long (with a 50-65 cm tail) and their weight ranged from 15 to 30 kg. They were characterized by long hind legs and several (13 to 19) dark stripes on rump and back that were unmistakable on a yellowish brown fur. They differed from dogs for a smaller cranium and the possibility to stretch the jaws to an incredible 90-degree gape. Thylacines were nocturnal hunter and they preferred to prey on wallabies, opossum, small kangaroos and birds. Being marsupials, the females had a pouch to carry the cubs (2 to 4).

This striped mammal inhabited the Australian mainland and New Guinea but the competition with the dingo caused the confinement in Tasmania. On this island, the “tigers” were hunted by Europeans because they considered this predator a threat to their sheep.

"I spotted a thylacine!"

Do the Tasmanian tigers still exist?

Photo: Peter Groves shared an image of an alleged Tasmanian tiger near Clifton Springs, Victoria - Credit: Peter Groves

Since 1936, there have been a lot of unverified reports

of sightings and not only in Tasmania, but also in mainland Australia. The Thylacine Awareness Group posted a video in 2016 asserting that it could depict a “Tasmanian wolf”. It was shot in the southern Adelaide Hills in Australia and it received more than 30,000 YouTube views. Neil Waters (Thylacine Awareness Group’s president) said that he was confident the video showed a thylacine but Catherine Kemper, South Australian Museum senior researcher, poured cold water on that claim.

"I think it would have to be extremely unlikely," she said.

Several surveys and researches led by naturalist and wildlife officials failed to observe a specimen of thylacine so far. In 2009, a team of geneticists declared that they had sequenced the genome of this species and they hinted at the possibility to clone the Thylacinus cynocephalus using the SCNT (Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer), transplanting the nucleus of a somatic cell from a thylacine into the cytoplasm of an egg from another species such as, for example, the native cat or the Tasmanian devil.

In 2017, Professor Bill Laurance (James Cook University, Australia) spoke with two people (one of them was an employee of the Queensland National Parks Service) who had seen, in two different locations and occasions, "curious" animals. The sightings took place in Cape York peninsula and Laurance himself stated:

“In one case four animals were observed at close range, with a spotlight.”

Richard Dawkins, the famous British evolutionary biologist, referring to those sightings said:

“Can it be true? Has Thylacinus been seen alive? And in mainland Australia not Tasmania? I so want to be true.”

During the field survey, the researcher Sandra Abell said the she had been contacted by other people who claimed to have spotted thylacines in that area. She decided to set up more than 50 camera traps to gather data to understand the status of endangered mammal species on Cape York peninsula and, at the same time, to try to detect the Thylacinus cynocephalus.

Abell stated that: “It is a low possibility that we’ll find thylacines, but we’ll certainly get lots of data on the predators in the area.”

She thinks that the "Tasmanian wolves" could be still out there:

“It’s not a mythical creature.”

Despite the efforts, the thylacine, if it is still alive somewhere, hasn’t been found yet but the sightings continue.

In 2018, two people, while they were visiting Tasmania, reported that encountered a “strange” creature: “(it) walked from the right hand side of the road, turned and looked at the vehicle a couple of times. It was in clear view for 12-15 seconds. The animal had a stiff and firm tail, that was thick at the base. It had stripes down its back. It was the size of a large Kelpie.”

A document from Tasmania’s Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE), printed in 2019, stated that they received eight possible thylacine sightings between 2016 and 2019.

A report from DPIPWE is dated July 2019 and it refers to a footprint found by an hiker that was walking up to Sleeping Beauty Mountain, Tasmania.

That same year, it is remarkable the testimony of a government plant biologist that told he saw a thylacine in a remote area, 30 meters (100 feet) from him.

Barry Brook, mammal ecologist at University of Tasmania, collected and analyzed the 1200 thylacine sightings from 1910 to 2019 and, assisted by his colleagues, created the Tasmanian Thylacine Sighting Records Database and used it to estimate the extinction date for this marsupial.

Surprisingly, their data indicated that the Thylacinus died out recently:

“Contrary to expectations”, the paper said, “the inferred extinction window is wide and relatively recent, spanning from the 1980s to the present day, with extinction most likely in the late 1990s or early 2000s. While improbable, these aggregate data and modeling suggest some chance of ongoing persistence in the remote wilderness of the island.”

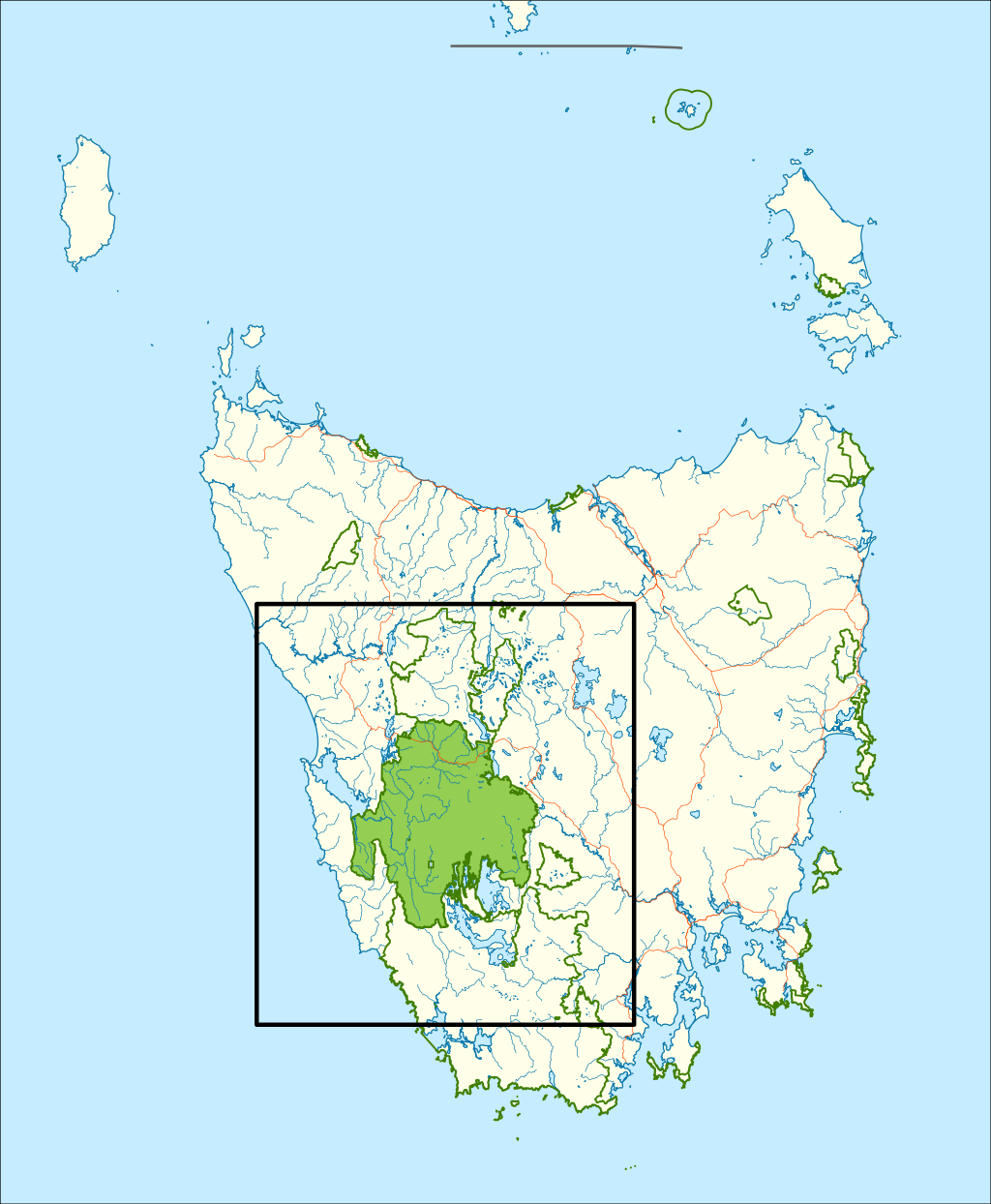

And what are these remote areas in Tasmania? If thylacines are still alive (or at least they were 20 years ago) they should roam the western and southwestern territories of the island such as, for example, the Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park and the Wilderness World Heritage Area. These areas are almost inaccessible and inhabited by pademelons and wallabies, two species that were probably predated by thylacines.

Photo: Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers national park within Tasmania - Credit: NeoGeneric, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Franklin Gordon Wild Rivers National Park,Tasmania - Credit: Nasher, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Other experts are less optimistic and they think that the search for the thylacine is “fruitless”.

A 2017 paper by the ecologist Colin Carlson, published in Conservation Biology estimated the chance that the "Tasmanian tigers" survived at 1 in 1.6 trillion. It also set an extinction date sometime between 1936 and 1943.

“The most optimistic scenario”, Carlson wrote, “suggests that it (the thylacine) did not survive beyond 1960.”

But in 2014, the vertebrate paleo-ecologist Dr Gilbert Price (University of Queensland), explored some caves in north Queensland and, inside one of them, he found several curious teeth.

“It was an amazing moment for me and something I’ll never forget”, he said, “they were the teeth of a thylacine.”

They were well-preserved and discolored but the crowns and roots were undamaged (very unusual for this kind of fossils).

“What if they were really young fossils?”, Dr Price thought, “what if they were from an animal post-dating 1936?”

And then we have the recent claim of The Thylacine Awareness Group, that announced to the world: we found a thylacine!

Here’s the video:

Nick Mooney, curator of the vertebrate zoology at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG), reviewed the images taken by the Waters’ group camera traps and concluded that: “based on the physical characteristics shown in the photos provided, the animals are very unlikely to be thylacines, and most likely Tasmanian pademelons”.

Nick Mooney studied the most credible sighting that happened in 1982 when Hans Naarding, a park ranger, said he watched one in front of him for three minutes. Naarding was sleeping before the moment he spotted the animal and several people considered it an illusion or a waking dream. Mooney concluded that it was hard to reach any conclusion but he added that he believed to a friend of him who had a similar encounter.

If Neil Waters and his crew had captured shots of a family of thylacines it would have been the most important wildlife re-discovery of the century, no doubt on that but, unfortunately, it seems that the "Tasmanian tigers" eluded us again.

So, does the thylacine still exist?

My opinion as a biologist is: maybe, it’s not impossible. Thylacinus cynocephalus was a misunderstood species hunted to extinction because they weren’t a real threat to sheep and human beings.

Sheep killer!

1£ for every thilacine slayed...

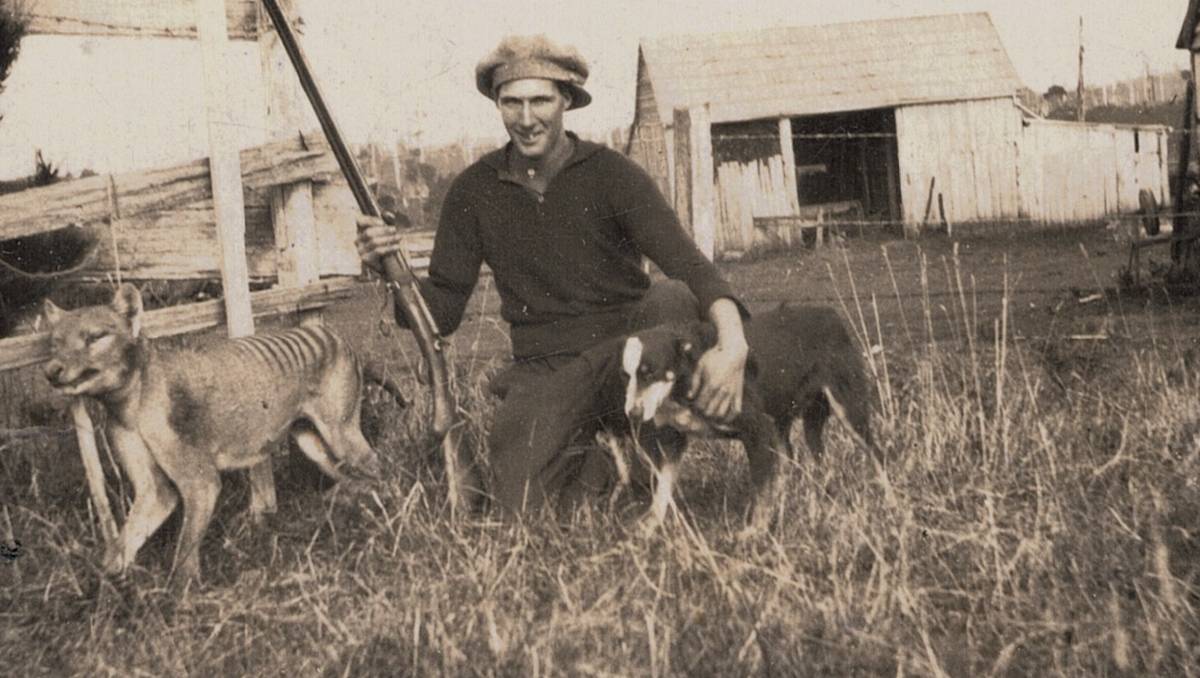

Photo: Wilfred Batty of Mawbanna, Tasmania, with the last wild Tasmanian tiger known to have been shot in the wild. He shot the tiger in May, 1930 after it was discovered in his hen house. Unknown author.

Europeans killed the first thylacine in 1805 and Lieutenant-Governor William Patterson wrote a letter to the Sydney Gazette declaring that:

“It is very evident this species is destructive, and lives entirely on animal food; on dissection his stomach was filled with a quantity of kangaroo. The form of the animal is that of a hyaena, at the same time strongly reminding the observer of the appearance of a low wolf dog.”

Gerard Krefft, one of Australia's first and zoologists and palaeontologists wrote:

“Some of the shepherds state that one of these animals will kill hundreds of sheep in a very short time, and instances are on the record of men having been attacked by them.”

"Tasmanian tigers or wolves" began to be considered as an enemy and were fiercely hunted and killed.

In 1850, naturalist John West wrote:

“The thylacine kill sheep, but confines its attack to one at a time; and is therefore by no means as destructive to a flock as the domestic dog become wild, or as the Dingo of Australia, which both commit havoc in a single night. High rewards have always, however, been given by sheep-owners for their destruction; and, as any available spot of land is now occupied, it is probable that in a few years this animal, so highly interesting to the zoologist, will become extinct; it is now extremely rare, even in the wildest and least frequented parts of the island.”

In 1888, for every killed thylacine, the hunters earned a bounty of 1£, the population collapsed and the last wild Tasmanian tiger was shot in 1930.

A research published in 2011 on Journal of Zoology and entitled “Skull mechanics and implications for feeding behaviour in a large marsupial carnivore guild: the thylacine, Tasmanian devil and spotted‐tailed quoll”, suggested that the thylacines predated especially on opossum and small Kangaroos and not on sheep.

Photo: Cradle Mountain, Tasmania. Many believe that thylacines still roam there.

Warren Darragh of the Thylacine Research Unit (TRU) thinks that the thylacine is probably extinct but he and his colleagues continue to analyze the best sightings and reports.

Camera traps are now widely used by scientists and Barry Brook, who has 500 to study mammals, said: “If it hasn’t been seen or photographed in the next decade, then we can really close the book on the thylacine. Never before have we had such an excellent opportunity to detect it.”

The thylacines may still be "lurking" somewhere in mainlad Australia or in Tasmania, it's improbable but, I repeat, not impossible. Anyway, we can learn from their demise, each time a species goes extinct is a tough loss for biodiversity and for the ecosystem in which it lived. I always repeat two words to my students in Russia: education and prevention. These two words are like a mantra for me and, if in the past it was complicated to educate people about the value of biodiversity and implement conservation plans, now we have the possibility to make a difference and save a lot of species that are, just like the thylacine a century ago, on the verge of extiction.

Maybe one day we will clone a specimen of Thylacinus cynocephalus or we will find one alive but, meanwhile, our efforts must be focused on saving or restore the balance of ecosystems to grant a future to an incalculable number of species, incluning ours.

Bibliography and Citations:

Paddle R. 2000. The Last Tasmanian Tiger: The History and Extinction of the Thylacine, Cambridge University Press, New York, US, 2002

M.R.G. Attard U. Chamoli T.L. Ferrara T.L. Rogers S. Wroe, Skull mechanics and implications for feeding behaviour in a large marsupial carnivore guild: the thylacine, Tasmanian devil and spotted‐tailed quoll, Journal of Zoology, Volume 285 Issue 4 Pages 292-300, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00844.x November 09 2011

Barry W. Brook, Stephen R. Sleightholme, Cameron R. Campbell, Ivan Jarić, Jessie C. Buettel, Extinction of the Thylacine, bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.01.18.427214 January 19, 2021

Colin J. Carlson Alexander L. Bond Kevin R. Burgio, Estimating the extinction date of the thylacine with mixed certainty data, Conservation Biology, Volume 32 Issue 2 Pages 477-483, doi:10.1111/cobi.13037

October 25 2017

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/animal/thylacine February 11, 2020

Dr. Price G., https://shorthand.uq.edu.au/small-change/is-the-thylacine-really-extinct/

Naaman Zhou, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/feb/23/wildlife-expert-pours-cold-water-on-claims-tasmanian-tiger-family-spotted February 23, 2021

Bressan D., https://www.forbes.com/sites/d... September 7, 2017

Fair J., https://news.mongabay.com/2021... February 4, 2021