Retracing old paths to an ancient home...

By Sofia Solovieva, Ph.D. Biol. Sci. IPEE RAS

Premise: This is the first non-academic text that I wrote as a Ph.D. Biol. Sci. for the Laboratory for Behaviour and Behavioural Ecology of Mammals, A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences. It is a new role and a new start in a new city (Moscow) and this article is a modified and shorter version of a project I just presented to continue a transboundary collaboration with Chinese colleagues, in order to study Amur leopards and tigers and the ecosystem they share with other large carnivores and a lot of different species. Enjoy the reading and wish me good luck!

Introduction

Leo 52M is an male adult specimen of Amur leopard, he is 9 nine years old and he has always been eager to explore new lands. From its home land in Primorsky Krai, he crossed the Russian border several times to reach China and there, the Feline Research Centre of China (FRC) camera traps, that were working in synergy with those of the Russian Land of the Leopard National Park (LLNP), captured him. Leo 52M was probably searching for a partner or trying to enlarge his home range but, even more important, he was not the only one Amur leopard that had decided to explore the territories of the “Red Dragon.” Another male, Leo 29, wandered between Russia and China 9 times during 2013-2014 and two females, Leo 63F and Leo 89F, crossed the border at least one time in two years. Two young leopards, a male and a female (Leo 81M and Leo 9F), were born in Russian territory but then they moved to China and they were observed, respectively, at 30 and 24 km from the border. It is very likely that they remained there and became resident suggesting an active dispersion of young individuals from the Land of the Leopard National Park to the Chinese forests.

Are the Amur leopards colonizing again a part of their past historical habitat? The answer is probably an yes even if there are several factors to consider before making a bold statement. But let’s proceed step by step starting with knowing something more about this elusive big cat.

A ghostly presence

Photo: Panthera pardus orientalis, Amur or Far Eastern Leopard.

The modern leopard species, scientific name Panthera pardus, originated in Africa less than a million years ago and then dispersed into Central and South-east (SE) Asia, Indian subcontinent and they reached the Far East. Among them, the species that spread into the easternmost offshoots of Russia “split” into a new subspecies: the Amur leopard.

Panthera pardus orientalis is one of the nine leopard subspecies, the northernmost and the rarest. It was first described by Hermann Schlegel, a German ornithologist and herpetologist, who examined a skin from Korea in 1857 and labeled it Felis orientalis. The Amur leopard, named also Far Eastern leopard, differs from other subspecies in its appearance and for the ability to survive in an extremely harsh and cold environment. The fur is lightly-colored, very thick (especially in winter) and up to 7 cm long. Large black spots are scattered on the entire body and they form an unique pattern that it is like a fingerprint to recognize each individual. This pantherid can move through deep snow because of its long extremities (the longest among leopard subspecies) and it is very shy and tolerant toward humans, especially if compared to other big cats species because not a single case of attack on Homo sapiens has been reported so far.

An adult male specimen can reach a length of 107-136 cm for a weight up to 80 kg and exhibit a long tail of 80-90 cm while the body length of an adult female is between 102-112 cm, the tail is 70-73 cm long and the weight is usually 40-45 kg. The Amur leopards are territorial and solitary animals, they use scent mark, or scratches, on trees to delimit their territory. They can live up 16 years in the wild and they consume 25-30 ungulates every year, especially sika deers (Cervus nippon), Siberian roe deers (Capreolus pygargus) and wild boars (Sus scrofa). Stalking the mixed coniferous-broadleaf forests, the Far Eastern Leopards can prey on more than 20 species, including birds, racoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides), Asian badgers (Meles leucurus), Manchurian hares (Lepus mandshuricus), rodents, amphibians and salmonid fishes. Small caves are often used by these big cats, females raise cubs there but they also serve as safer places to rest. Amur leopards are very conservative in their choices and they prefer to use the same paths, dens and passages. For this reason, activities such as road constructions or dwellings that alter the habitat have a disruptive impact on these big cats forcing them to leave the territory to find another one.

Sexual maturity is reached at the age of 2.5-3 years and the females are able to breed throughout the entire year (even if it usually happens in spring) and they give birth after a 90-95 days gestation. The cubs stay inside the den for 1-2 months and then, after 16 months, they leave the mother and start exploring new areas. Using the radio telemetry and even if it can vary depending on several factors (density of ungulates, presence of Amur tigers or other leopards in the same zone), biologists have quantified the size of Amur leopards territories: up to 100 km² for females and up to 300 km² for an adult male.

Panthera pardus orientalis’ historical range covered the combined territory of Primorsky and Khabarovsk Krais, Northwest (NW) of China (Jilin and Hailongjiang provinces) and the entire Korean Peninsula. The population decreased from the beginning of the 20th century due to habitat destruction and fragmentation, poaching, conflicts with men and industrial development. The Amur leopard was on the edge of extinction in the early 2000s, only 35 individuals remained and they were like doomed “ghosts” that walked silently the South-west (SW) of Primorsky Krai.

The incredible efforts of biologists, ecologists and environmental organizations and conservation programs gave this species a hope and, slowly, it started to invert the population reduction negative trend. In 2012, a National Park was established in the Primorsky Krai, they named it The Land of the Leopard National Park and, immediately after its creation, one of the oldest nature reserves in Russia, The State Nature Biosphere Reserve Kedrovaya Pad (created in 1916 and member of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves), joined it to create a protected area of 286 thousand hectares. “Land of the leopard” borders China in the west and North Korea in the south and, including the districts of Khasansky and Ussuri and part of the Nadezhdinsky’s, it covers almost the entire modern habitat of Amur leopard. In Korea, there are no recorded sightings of Panthera pardus orientalis since 1969 but it is almost certain that this species is coming back to some Chinese provinces bordering the Russian Federation. From August 2012 to July 2014, 380 camera traps scattered in an area of 6000 km² in NE China, photographed 42 leopards of which 37 were moving within 5 km from the border. During the same time frame, the Land of the Leopard National Park 400 camera traps set in the Primorsky Kray, captured at least 70 individuals and clearly showed a remarkable population growth. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species still lists the Amur leopard as Critically Endangered (CE) but the last count made by the “Land of the leopard” experts provided an estimate of 97 specimens present right now in the Russian territory and that number means that, since the creation of the Park, the population has grown up thrice. These data are reassuring and give us the measure of the leopards resilience and capacity to survive even in an environment inhabited by the most dangerous creature on Earth, the diurnal primate species called Homo sapiens, and the most efficient terrestrial predator: the Amur tiger.

A cat of 250 kg

Photo: Panthera tigris altaica, Amur Tiger.

Panthera tigris altaica is the scientific name of this rare subspecies of tiger. It is the largest in the feline family and the undisputed ruler of the Ussuri taiga, capable of preying on every species that shares its habitat, from a little amphibian to a large brown bear. Tigers evolved in tropical Asia before moving towards north and the Amur subspecies still occupies the northern limit of this species’ range, it has always experienced extreme environment conditions but it is equipped with peculiar characteristics to obtain the top of the food chain. Adult males individuals are way bigger than their female counterparts exceeding 120 cm in height (at the withers) and 2 meters in length (tail excluded) for a weight of about 180 kg. The heaviest Amur tiger recorded in the wild was almost 250 kg, a real fearsome giant. The size of an adult female is, usually, 180 cm in length for 160 kg of weight. This tiger differs from the other subspecies for its dense, thick and long fur, a fundamental feature to survive the Russian Far East endless winter.

While the Amur leopard prefers to live in mixed coniferous broadleaf forests that range from the coastal area to 800 meters above the sea level and that are characterized by the presence of hills and exposed cliffs, the Amur tigers tend to inhabit cedar pine, oak and less frequently even riparian forests adjacent to a river, stream, lake or pond. Both these two big cats are extremely territorial and solitary but tigers show a “low biotope selectivity” and their average-sized habitat range is wider: more than 1300 km² for an adult male and 400 km² for an adult female.

The lifespan of an Amur tiger is between 15 and 20 years, the females can breed when they reach 3.5-4 years and, usually every 2,5-3 years, they give birth after 95-120 days of pregnancy.

Very few animals have a chance against a full grown Amur tiger. Its offensive arsenal is impressive: each jaw has 14 teeth, 4 of them are sharp canines 7.5 cm long and, after a silent stalking, a Panthera tigris altaica can jump up to 5 meters in height and up to 9 meters in length from a still position to grab its prey and choke it to death. Amur tigers can eat everything but, just like the leopards, they prefer hoofed animals whose size equal or exceed their own: red deer, roe deer, sika deer and wild boars. For an adequate nutrition, an adult tiger would need of 50-70 ungulates a year but this big cat can easily change its preys and, for example, feed on badgers or racoon dogs and survive in different habitats.

Almost the 95% of the entire Amur tiger population is concentrated in Russia in two Krais, Primorsky and Khabarovsk, and in the two Oblasts, Jewish Autonomous and Amur. In the past, it was widely distributed throughout NE Asia but, from the early nineteenth century, it was plagued by an intensive and unregulated hunting that caused a decline in the population and fragmented the habitat, including the main one in the Sikhote-Alin Mountains. In the decade 1930-1940 only 30 tigers were present in Russia and their disappearance seemed imminent. Things started to change in 1947 with the implementation of the ban on the Amur tiger hunting and the laws against the trade of animal part to Asian markets that stabilized the population. From the core area in the northern Sikhote-Alin, tigers began to expand and recolonize the lost territories while their numbers increased: by 1960 there were 100-110 individuals, in 1970 the experts estimated 150 specimens and, according to two counts occurred in 1995-1996 and in 2004-2005, the Amur tigers reached the 450 units.

The Ussuriysky Nature Reserve, the Sikhote-Alin and the Lazovsky Nature Preserves were established in 1934 and 1935, the first three protected areas in that part of Far Eastern Russia that were followed by other eight: Botchinsky Nature Reserve (1994), Bastak Nature Reserve (1997), Anuyskskiy National Park (2007), Call of the Tiger National Park (2007), Udege Legend National Park (2007), Land of the Leopard National Park (2012), Bikin National Park (2015). The protection granted by these areas and the safeguard and conservation programs created the conditions that helped tigers and leopards to continue to increase their number and, in 2015, the biologists counted 540 specimens of tigris altaica in Russia.

Before going into details about the Amur tiger and leopard comeback to China, it could be useful and interesting note that, at the end of the nineteenth century, more than half (about 1500 individuals) of total Amur tigers lived in the Land of the Red Dragon. The collapse of the Qing Dynasty and the subsequent removal of the ban on forest exploitations, altered the habitats and the number of these pantherids fell down. In 1930, they were 500 and, in the decade 1950-1960, tthey stopped inhabiting the Xiaoxinganling range. The Amur tiger still resisted in the mountain forest of Yanbian and near the Mudan and Songhua rivers in Heilongjiang Province but, overtime, its habitat range continued to shrink and, in 2003 and 2004, only 20 specimens were reported in Northeast China and no more than 10 lived in several isolated places.

“Reconquering” their previous historical territories it is fundamental for Amur tigers and leopards, recent sightings of these animals along the China-Russia border encouraged some biologists to start several studies to determine if the two felids are coming back to North-east China to stay, what factors are influencing their choices and if it is possible to propose a long-term conservation plan.

The “Amur tigers and leopards returning to China: direct evidence and a landscape conservation plan” study (1)

An interesting multi-authored research monitored the two big cats, their preys and the interactions with human activities using 380 camera traps stations over an area of 6000 km². It took place in NE China, more precisely in Heilongjiang Provinces and in the northern portion of the Changbai Mountain in Jilin, territories that include the Laoyeling Reserve, Hunchun Reserve, Wangqing Reserve, Hunchun Forest Bureau Land and that border the Primorsky Krai and the North Korea. The study lasted two years (2012-2014) and the camera traps were placed along the most common natural routes followed by tigers, leopards and their preys. After 175,127 days, they analyzed the data and obtained the following results.

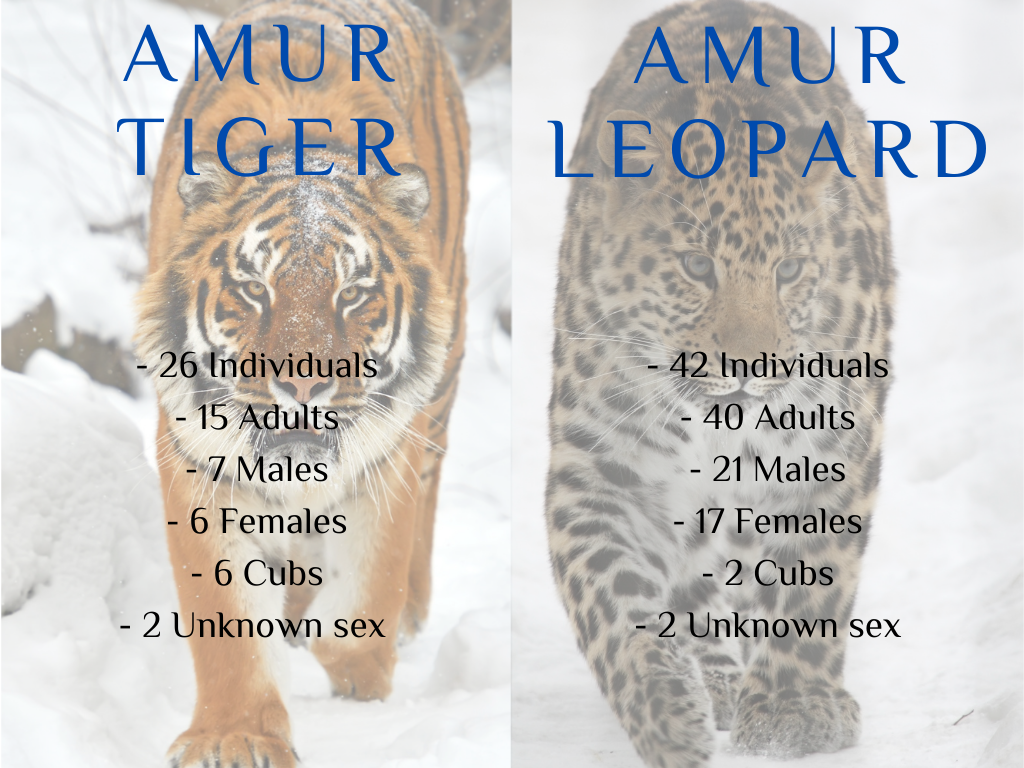

Photo: Number of Amur tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) and Amur leopards (Panthera pardus orientalis) in NE China identified in 2012-2014 field study with camera traps. (1)

Since 1998, after that The Natural Forests Protection Program improved the quality of wooded areas in China, reports of sightings of tigers and leopard started to increase. The study area is a good habitat for these large carnivores, filled with Korean pines (Pinus koraiensis), birches, oaks and the elevation ranges from 5 to 1477 meters. Are these zones frequented by potential preys? The answer is an yes: sika deer (Cervus nippon), Siberian roe deer (Capreolus pygarus) and wild boar (Sus scrofa) are the most common ungulates that inhabit the study area.

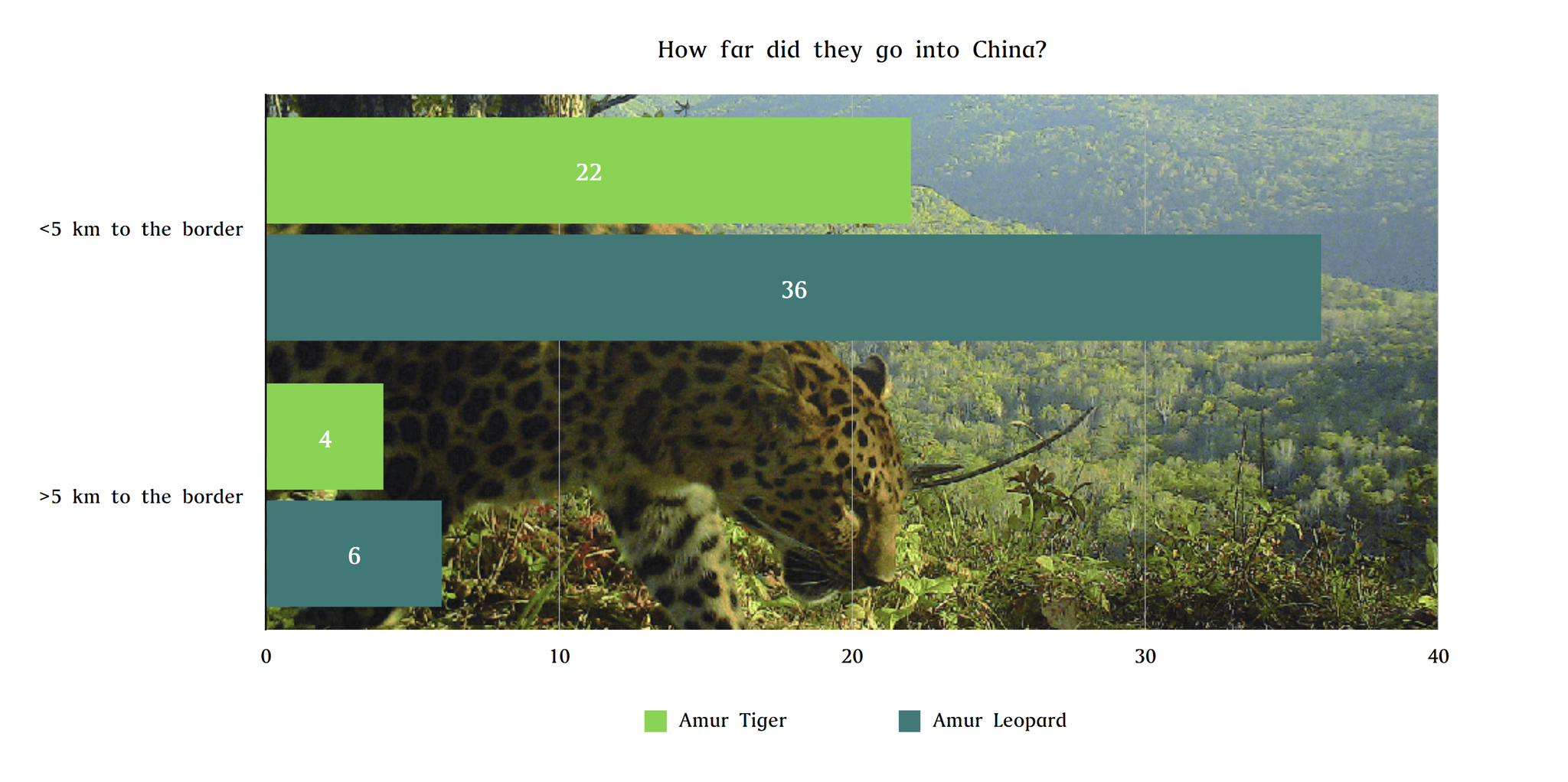

The numbers show that several tigers and leopards cross regularly the Russia-China border and move into a territory that could be suitable for them. But how far are these pantherids penetrating into China?

Photo credit: Beijing Normal University

What did prevent them from going further inward? The reasons were:

- The study area is wooden but interspersed with several farmlands, villages and cultivated zones. That means roads and human activities.

- The two primary preys, red deer (Cervus elaphus) and Sika deer (Cervus nippon), were either absent or present in an area within 5 km from the Russian border.

- Cattle grazing were widely distributed.

The study clearly indicates that a resident and stable population of tigers and leopards in NE China needs an unfragmented habitat, where these carnivores can find preys and shelters. Cattle grazing is probably the more severe obstacle they have to face, it impacts on their movement patterns and reduce the availability of their preys because the larger and stronger cattle have a competitive edge over the sika deer.

I decided to cite this research because it was the first one that provided a direct and documented evidence of the return of Amur tiger and leopard in China. Both species crossed the border, frequented the study area but found several hurdles that made the resettlement unlikely.

Before writing about what kind of actions should be taken to create the conditions for a resident population of Panthera tigris altaica and Panthera Pardus orientalis in NE China, we will take into account another, and newer, study conducted by the Land of the Leopard National Park researchers in collaboration with Chinese biologists and experts.

The Sino-Russian collaborations (2) (3)

In 2016, the Felice Research Centre of China (FRC) exchanged its camera traps data with those obtained by the Land of the Leopard National Park (LLNP) to compare the results of their surveys conducted from 2013 to 2015. The Russians downloaded the images captured by 314 camera traps installed in 157 different points while the Chinese visioned the photos shot by 634 camera traps set in 317 locations. The spots on leopard’s body and the tiger’s stripes are like our fingerprints, you won’t find two individuals with the exact spots or stripes pattern and, since it is also asymmetrical on the left and right side, to capture a both sides image of the animals, they positioned two camera traps at every site.

The analysis was made using a manual method (visual comparison of spot/stripe patterns by an expert) and then integrated with the aid of an algorithm by the so called Extract-Compare software.

Comparison Chart: Amur Leopards and Tiger individuals captured by the FRC and LLNP Camera Traps

In addition to the above data, it is noteworthy to add that:

- 10 breeding Amur leopard females and 6 breeding Amur tiger females were observed in both countries.

- One leopard female was captured in China with 2 cubs (one still lives there) while in Russia they found evidence of 9 females with offspring (19 in total).

- 16 cubs of 6 Amur tiger females were captured in Russia, 3 were born in China and 6 born in Russian territory used to cross the border.

- Several leopards wandered in NE China, we have already talked about Leo 52M, Leo 29M and the females Leo 63F and Leo 89F (take a look at the Introduction), but even tigers did that regularly. CT1, CT2, CT16 and CT17 crossed the border at least 3 times, CT5 was observed with 4 cubs in Russia and then, almost a year later, with 2 in China. CT5 was caught at 36.3 km from the border and CT26 ( a cub of the female T1) was observed alone as an adult at 30.6 km into the Chinese territory. These examples indicate a positive dispersion trend of females with cubs and young individuals from Russia to China.

In the fall 2015, the LLNP signed an agreement with Beijing Normal University China (BNU) for a transboundary collaboration in tracking the individuals of Panthera tigris altaica and Panthera pardus orientalis and their movements. They positioned 536 camera traps in the South-west Primorsky Krai and in the near Chinese Jilin Province. The study revealed 92 Amur leopards in China and Russia (32 males, 43 females, 4 unidentified adults and 13 cubs) and nearly 38% of all leopards were observed in China but only 20% were spotted exclusively in that Country. Most of Amur leopards still frequent and live in Russia and don’t travel towards China but there was an extensive movement of individuals between the two Nations. The same research identified 38 Amur tigers coexisting with the leopards in the same areas.

This transboundary cooperation showed that a recovery of Amur leopards is happening in the Chinese territories along the Russian border. Even if there is a barber-wire fence between 200 and 10,000 meters from the Russian perimeter, camera traps showed that leopards and tigers crossed it. Border fences divide populations and they are an obstacle to wildlife movements but, in this case, the real barriers are the political ones.

The results obtained by Russian and Chinese biologists give credit to those experts (Bischof at al. 2016 and Gervasi et al. 2016) regarding the overestimation of carnivores populations along the borders if the count is made by a single Country. Collaboration increases the precision and provide a strong support for further studies.

The road is traced and we must continue to follow it

The three studies and the data obtained show that Amur leopards and tigers are trying to expand their habitat moving to NE China. Lately, have been recorded sightings of these two big cats even in the northern parts of North Korea. Several specimens crossed (and they are still doing it) the border and reached the forests of Jilin and Heilongjiang Provinces, some individuals chose to remain there and the creation of small populations is probable if some conditions will be assured.

A long-term collaboration between Russia and China is the key to save these subspecies. Amur leopard and tiger recovered from a point of no return but they are still threatened and their future is linked with the recolonization of the previous habitats. To grant it, there are several steps to do:

- A continuous cooperation between Russian and Chinese biologists, ecologists and experts to monitor the activities of these pantherids.

- It is important to join the efforts to fight the illegal trade of animal parts and derivates that still plague tigers and leopards.

- Educating people and communities that live in the territories frequented by large carnivores is crucial in order to create a “tiger and leopard awareness”, the ignorance is always the worst enemy to beat.

- Tiger and leopard conservation should be incentivized involving local communities and it is achievable improving innovative mechanisms such as carbon credits or direct paying for services made by local people that have a positive environment effect.

- Cattle grazing is the main obstacle to Amur tiger and leopard expansion toward China because it affects their spatial distribution and reduce the number of sika deer (even if tigers prey on livestock and this is another reason for conflicts with men).

The good news is that something has already been done.

Since 2015, it exists a joint working group that could become a transboundary management of the area between Russia and China, leading new researches and conservation programs.

In 2017, President Xi supported the creation of a new national park that bordered the Russian territory where tigers and leopards were already protected. BNU research team had sent him a proposal after the co-study with LLNP experts and he agreed with them: the pantherids need more space and a larger unfragmented habitat. The new protected area was called: the Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Park and it was 60% larger than Yellowstone National Park.

The cooperation between Russian and Chinese biologists/ecologists and their studies were the flame that fired an historical collaboration aimed to save two subspecies and the ecosystem they inhabit. Investing in nature conservation is always a win-win but it can last only if local communities are included and made protagonists.

In 2019, the Land of the Leopard National Park and the Chinese National Park made an agreement to create a single national park called “Land of Big Cats”, the first transboundary protected area for Amur leopards, tigers and a lot of other species.

Leopards habitat in Russia is fully occupied, sub-adults need new territories to explore and colonize to ensure a healthier genetic variability. It is the same for Amur tigers and, in their case, the expansion of the population is possible with the creation of an ecological corridor to the Sikhote-Alin Mountains (their core area in Russia).

The role that large carnivores play for the ecosystem is irreplaceable, the cooperation between Russia and China to ensure the surviving of Panthera tigris altaica and Panthera pardus orientalis is something of capital importance and other Nations should follow their example. It is possible to coexist with tigers, lions, leopards, wolves, bears, they can generate wealth and improve the wellness of human communities but they are mostly the key factor for an healthy ecosystem. We are part of it just like every other species, we thrive if it thrives and we perish if it dies.

Russia needs tigers and leopards and China too, they are recovering and coming back, hear them roar and remember:

“Nature remains in harmony; a natural balance is maintained. Large predators are an indicator of the state of the ecosystem: if the number of cats is stable, if they feel comfortable, then the nature as a whole is healthy."

Viktor Bardyuk, director of the “Land of the Leopard”.

Bibliography:

(1) Wang, T., Feng, L., Mou, P. et al. Amur tigers and leopards returning to China: direct evidence and a landscape conservation plan. Landscape Ecol 31, 491–503 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0278-1

(2) Elena Shevtsova, Guangshun Jiang, Anna Vitkalova, Jiayin Gu, Jinzhe Qi, Marina Igorevna Chaika, Valentin Yurievich Guskov, Yao Ning, Meng Wang, Alexey Kostyria and Yury Darman, Saving the Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard, NEASPEC, 2018 http://www.neaspec.org/sites/default/files//2018_12_17_UNESCAP_%ED%98%B8%EB%9E%91%EC%9D%B4.pdf

(3) Vitkalova, AV, Feng, L, Rybin, AN, et al. Transboundary cooperation improves endangered species monitoring and conservation actions: A case study of the global population of Amur leopards. Conservation Letters. 2018; 11: e12574. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12574

Feng, Limin & Shevtsova, Elena & Vitkalova, Anna & Matiukhina, Dina & Miquelle, Dale & Aramilev, Vladimir & Wang, BNU_tianming & Mu, Pu & Xu, Rumei & Ge, Jianping. (2017). Collaboration brings hope for the last Amur leopards. Cat News.20. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.1...

Hebblewhite M., Miquelle D. G., Aramilev V. & Pikunov D. 2011. Predicting potential habitat and population size for reintroduction of the Far Eastern leopards in the Russian Far East. Biological Conservation 144, 2403-2413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioc...